Project

Motivation

From Zika and Ebola to HIV and H1N1, viruses have always been a key point of focus for the medical community. What makes viruses an especially deadly foe is their fast rates of mutation, which can render current antiviral therapies useless in the blink of an eye. For example, consider the common flu. Every year, flu vaccines must be redesigned to ensure that they will be effective, and even with this method, the vaccines are not foolproof. Earlier this year, Australia experienced the biggest flu season on record, with Queensland experiencing the highest number of flu-related hospital admissions in the past 5 years[1].

Diagnosis is the first step to fighting viral infections

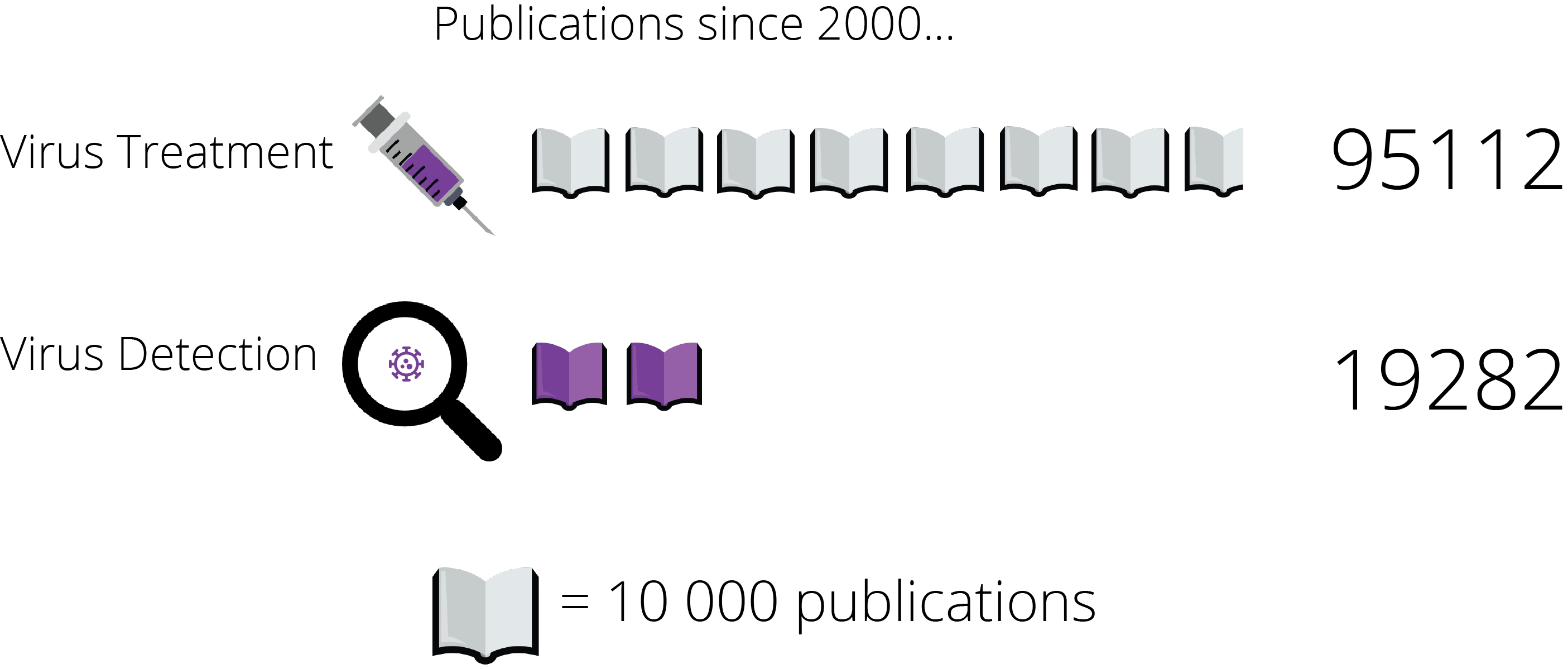

When a patient comes in with a suspected viral infection, the virus must be detected and recognised long before any treatment can be administered. While seemingly obvious, this fact is often overlooked in research. Despite huge advancements in antiviral therapy, viral detection methods have changed little over the past years. Using databases provided by the University of Sydney Library, a search using the keywords ‘virus treatment’ yielded 95,112 academic publications since 2000, yet a search using the keywords ‘virus detection’ yielded a scant 19,282 papers.

This remains a serious impediment to our ability to treat viral infections. A paper published in 1989 reported that physicians avoided using viral detection laboratories at hospitals due to the long wait before results could be obtained, and the high cost needed for viral detection tests[2]. The situation today has not changed.

An ideal method for viral detection would be:

- Easy to use

- Low-cost

- Capable of providing fast diagnosis

This became the motivation for our project.

Background and design

Our project aims to produce a system for viral diagnosis that is easy to use, low-cost, and is able to give a result on the spot. Our solution consists of two steps: amplification and detection.

Amplification

As viruses are packets of DNA, viral DNA is usually present in samples of blood from an infected patient, and we can use this DNA as a target for detection. However, this viral DNA may only be present in trace amounts, making it extremely difficult to detect. Amplification is needed to turn this trace DNA into a larger signal that can be detected by our device.

The classic method of amplification is polymerase chain reaction (PCR). In this method, an enzyme known as Taq polymerase produces many copies of the viral DNA, thus increasing the amount of viral DNA that we can detect. This sounds pretty amazing, but PCR has a drawback when it comes to point of care testing, particularly when used in remote or epidemic stricken areas. The machine may not been able operate due to lack of power, flood or some other environmental hurdle.

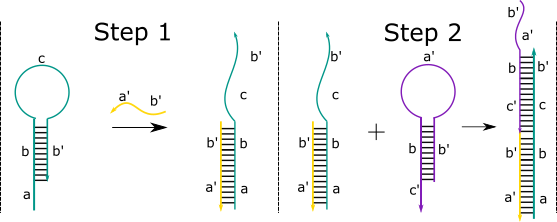

An alternate method that has been proposed in DNA amplification is hybridisation chain reaction (HCR). HCR was originally introduced as a linear process; A DNA hairpin binds to a single stranded strand of “trigger” DNA, viral DNA in our system, which causes the hairpin to open up. The exposed toehold binds to a second hairpin, which in turn opens up. This process continues linearly until a long strand of DNA consisting of many shorter strands is formed. Recently, nonlinear HCR has been investigated[3].

In our design, the viral DNA first passes through an adaptor to release the trigger strand. This strand interacts with a double stranded sequence. Substrate A subsequently interacts with a helper, a strand that helps displace the desired target strand fed into the detection system. This in turn binds to another double stranded sequence with another helper. Which, finally, binds to a third double stranded sequence with another helper sequence. This process releases three target strands and repeats to give one, large dendrimer molecule and a lot of target strands for very small amounts of viral DNA.

These target strands are detected by the detection system, turning the signal into an colour change visible to the analyst.

Detection

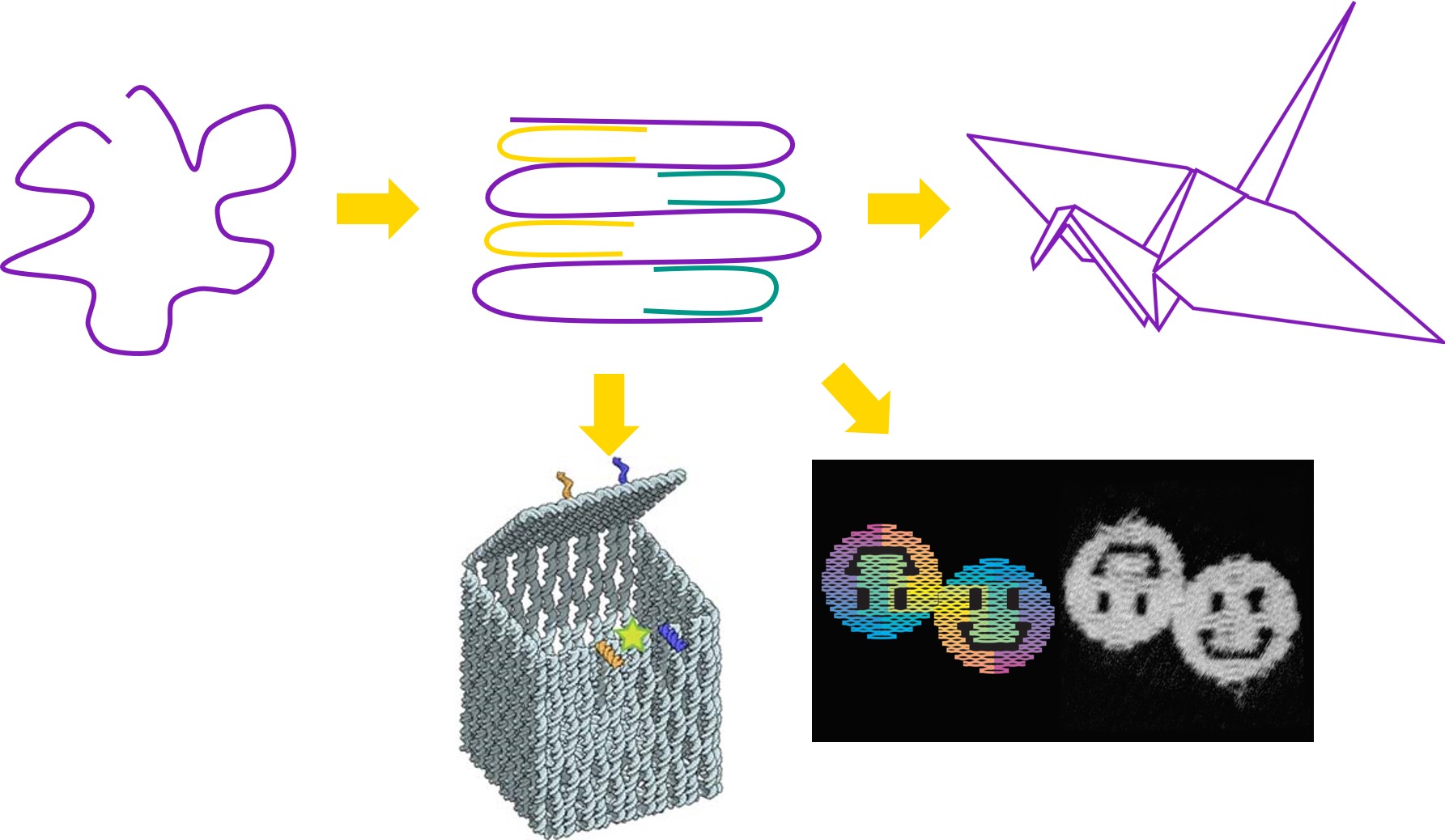

DNA occurs on the nanoscale – this means that even after amplification, we are unable to see the viral DNA with our naked eyes. A device is needed to turn the amplified signal into a visible colour change. In our project, we use a technique called DNA origami to make a switchable device out of DNA.

What is DNA origami?

|

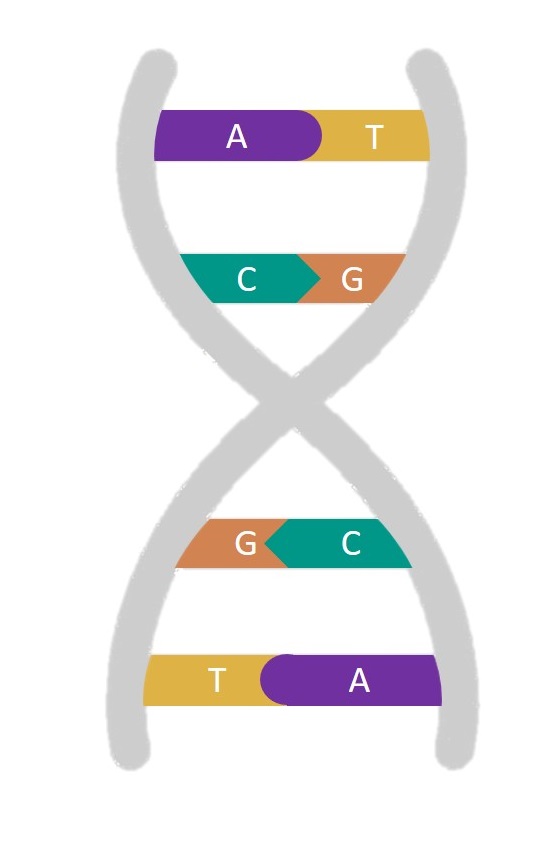

DNA origami is a technique that uses DNA as a building material. It takes advantage of the specificity with which DNA base-pairs; adenine with thymine, and cytosine with guanine. |

This means that we can design strands of DNA with specific sequences of bases, such that when mixed together under the right conditions, the DNA will self-assemble into a structure determined by the DNA sequences used. While the first conceptualisation of this technique back in 2006 was only capable of making 2D shapes and patterns such as smiley faces and triangle tiles[4], this technique has since been expanded to produce extraordinarily complex 3D structures such as boxes with controllable lids[5].

Why use DNA?

DNA has proven itself as an ideal structural material, for many reasons.

- Low cost: DNA is a relatively cheap material. Simply by sending an online order with the desired sequences to companies such as IDT, the strands can be produced and shipped over within days at low costs.

- Thermostability: DNA structures are stable over a larger range of temperatures. This means that unlike other common biomolecules like proteins, DNA structures do not have to be stored at near-zero temperatures, and have an incredibly long life. The lack of need of specialized storage equipment not only lowers the cost of making and using DNA structures, but also makes them more accessible in places where funds are an issue.

- Ease of use: The stability and low toxicity of DNA means that specialized training is not required to be able to deal with DNA structures.

For these reasons, DNA origami has been established as a valuable technique in an immense range of fields. For example, DNA origami has been used to design devices for targeted drug delivery[5], scaffolds for protein folding[6], and even molecular computing[6].

In this project, we use DNA origami to make a DNA structure that detects a signal, changes conformation and releases a dye molecule to produce a visible colour change in response to the signal. The signal in question is the presence of viral DNA, and thus this DNA structure acts as a viral biosensor.

Our device mimics paper origami.

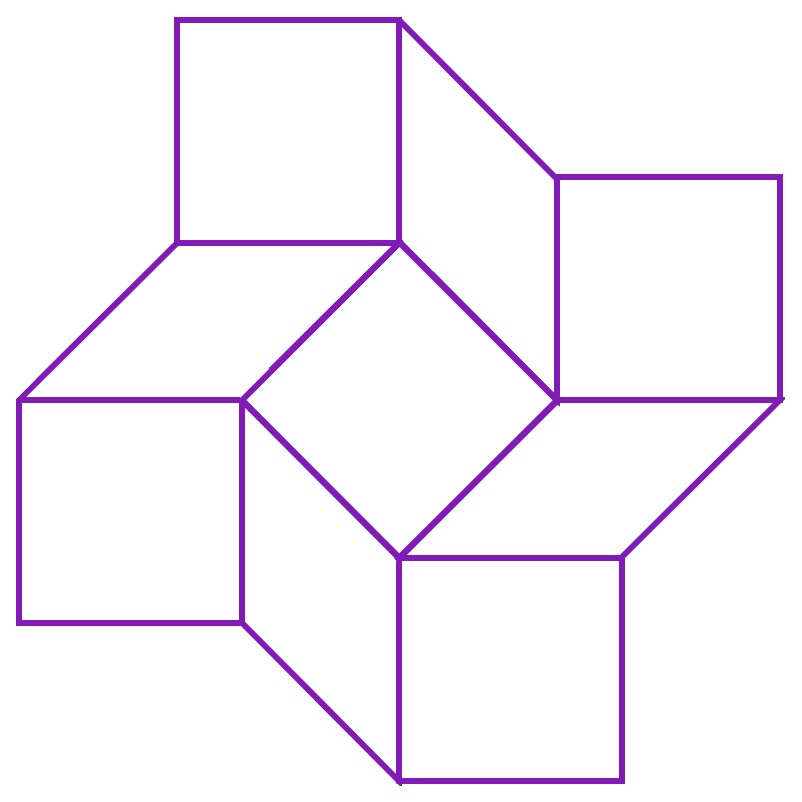

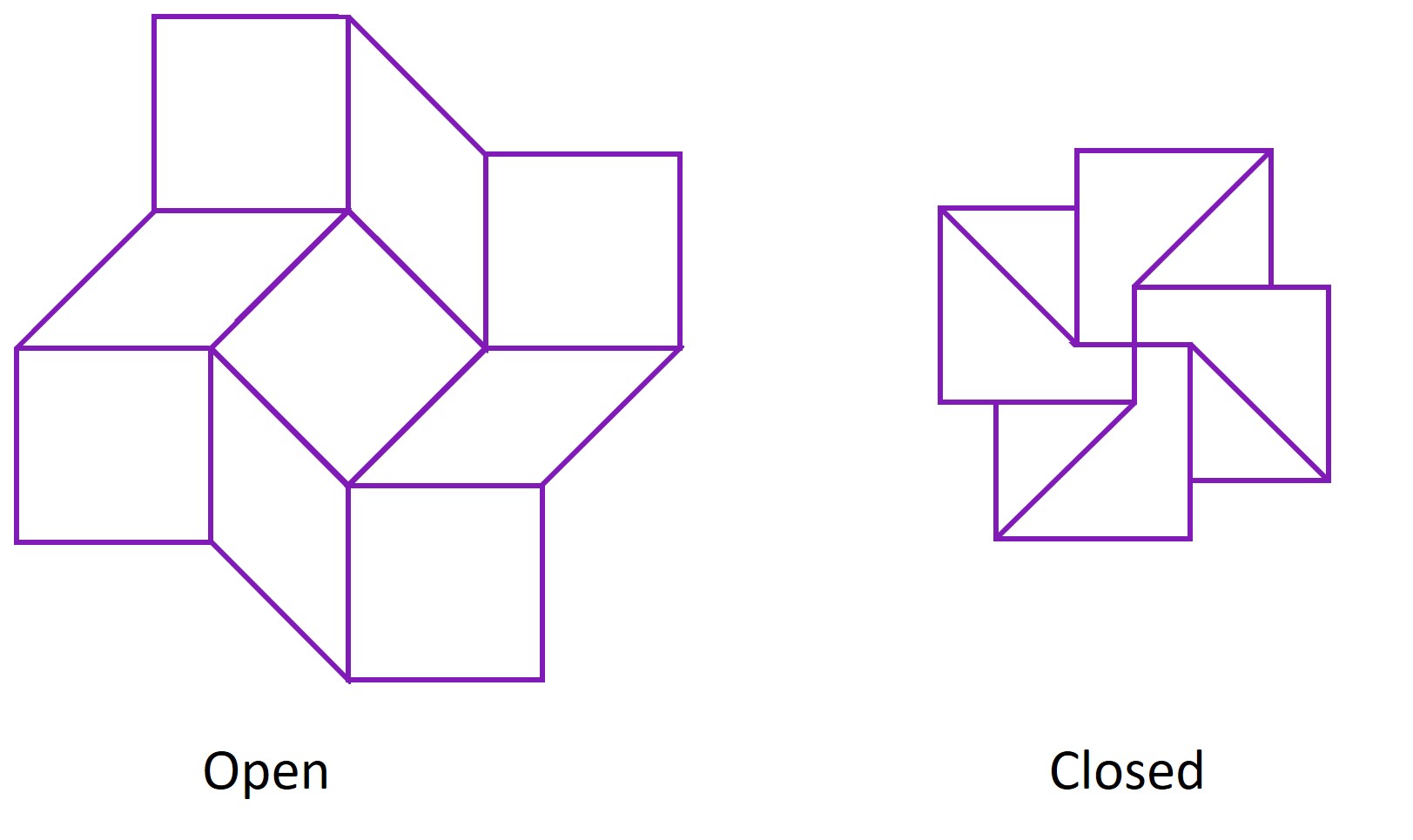

We folded DNA into a large, flat sheet, in the following shape. The lines represent where the sheet is thinner, and can thus fold.

In paper origami, this pattern is known as a square twist. It allows the paper to exist in 2 conformations - a closed conformation and an open conformation. The square twist is most stable in either of these conformations, and cannot exist in any state in between the two conformations. Hence, if one pulls the edges of the closed square twist open with sufficient force, it ‘snaps’ to the open conformation, and if one pushes the edges of the open square twist together, it ‘snaps’ back to the closed conformation.

Hence, the square twist behaves like a switch that can only be in the ‘off’ or ‘on’ state. By making the square twist out of DNA, we intend for it to act as a switch on the nanoscale, one which is naturally ‘off’, but turns ‘on’ in the presence of viral DNA to produce a visible colour change. In other words, we are performing paper origami on a sheet made using the technique of DNA origami. There is a certain irony, but not an unsatisfying one, in this concept.

How does the origami produce a colour change?

The DNA device start off in the open conformation, and is held open by a brace; a long strand of DNA hybridized to a complement strand. The amplification system detects viral DNA, and produces an amplified signal in the form of a trigger strand, which binds to the complement strand. This displaces the complement strand from the brace, leaving the brace single-stranded. This brace is designed to preferentially fold into a hairpin when single-stranded, and this provides the force needed for the square twist to change to the closed conformation. The closing of the square twist brings two complementary sticky ends into proximity, one of which is initially hybridized to a dye-bearing DNA strand. The sticky ends bind and displace the dye-bearing strand, which is washed away. The removal of the dye-bearing strand results in a visible colour change.

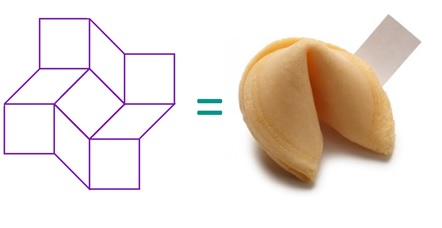

What do we call this device?

During our meetings, we realised that what we were attempting to build was a foldable object that could tell you whether you had a viral infection or not - in some ways, this could be seen as telling your fortune. It came to mind that there already exists a folded object that tells one’s fortune - a fortune cookie! For this reason, our device has since been dubbed the ‘fortune cookie’.

Integration into a chip-based system

Having designed an amplification system that amplifies viral DNA into a large, detectable signal, and a device that can translate that signal into a visible colour change, we have conceptualised a system for the detection of viruses. To make this system of practical use, the system is intended to be contained within a chip, such that one only needs to inject a sample from a patient into the chip to diagnose the patient with a viral infection. The successful creation of this chip is the ultimate endpoint of our project.

Is this system meritable?

The system we have envisioned is a novel solution to the problems faced in viral detection today.

-

Speed: This system acts as a means of rapid, on-the-spot diagnosis that can be performed immediately at the bedside. This allows the patient to receive appropriate treatment faster.

-

Simplicity: As both amplification and detection are integrated into a single system, the system acts as a direct bridge between obtaining a sample from the patient and producing a diagnosis, without any intermediate steps. The system is also designed to be exceedingly easy to use - only the simple injection of the sample into the chip is necessary to obtain a result.

-

Cost: As the entirety of the system is made of DNA, it is projected to have low production costs. Compared to existing viral detection methods, our system is made all the more cost-efficient due to the lack of need for storage equipment, processing equipment or specialized training.

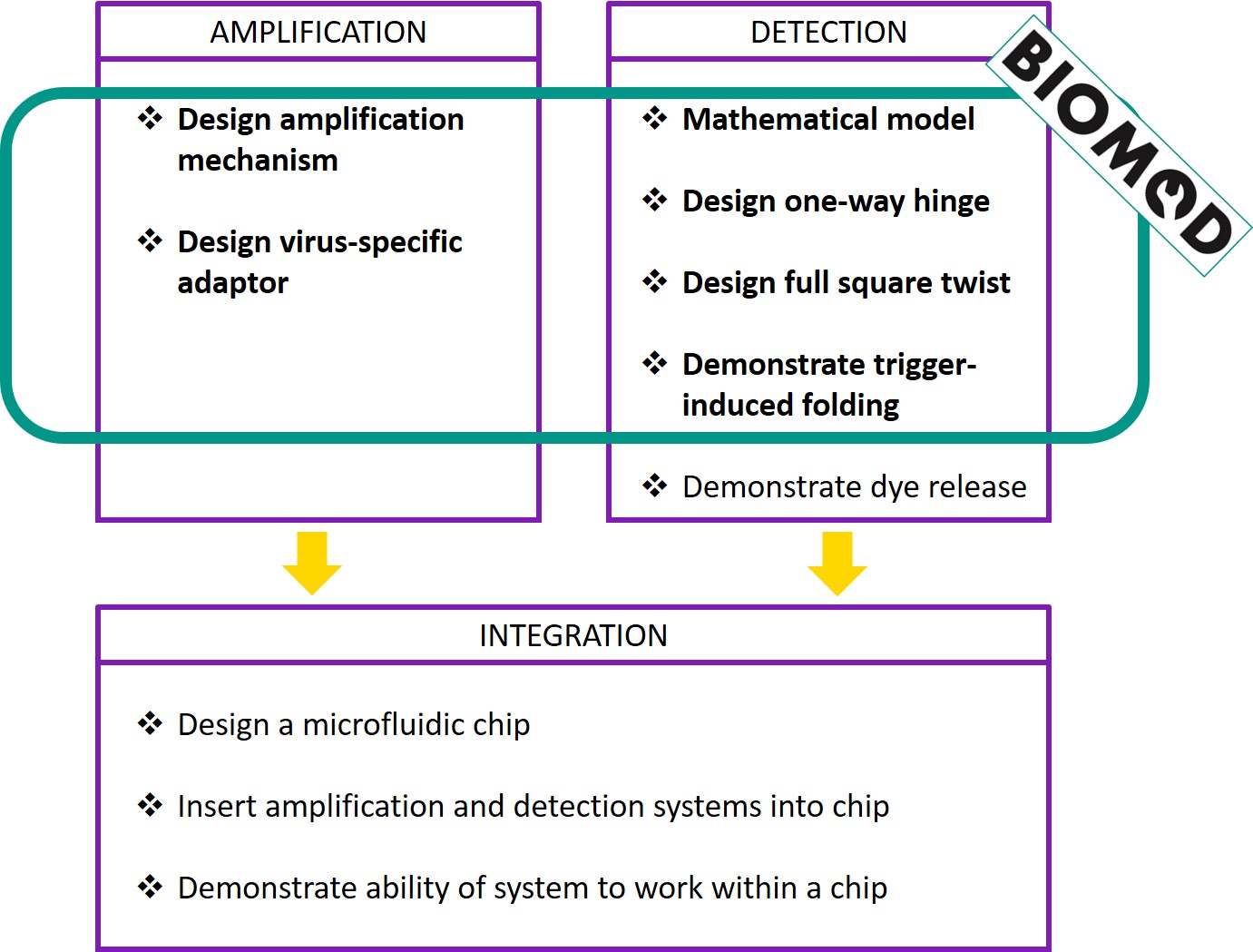

Goals

The ideal goal of our project would be to produce the chip described above, capable of reading a patient sample and diagnosing a viral infection within seconds. To achieve this goal, one would have to move through several intermediate stages of testing. However, given the timeframe of BIOMOD, it would be unfeasible to attempt every stage. Hence, we have identified the first few stages as our primary aims, so as to produce a proof of concept of the system.

Checklist for success

-

Amplification

- Design an amplification system

- Does the system complete the amplification process in under 60 minutes?

- Is the system stable in the absence of viral DNA?

- Does the system not produce any false positives?

- Design a virus-specific adaptor

- Can the system recognise specific viruses?

- Design an amplification system

-

Detection

- Mathematical model

- Does a square twist made of DNA behave the same way as a square twist made of paper?

- Design a one-way hinge

- Does the structure fold successfully?

- Does the hinge work - can the hinge open and close?

- Is the hinge one-way - is the motion of the arms of the hinge restricted within a range of angles?

- Design a full square twist made of DNA

- Does the structure fold successfully?

- Demonstrate trigger-induced folding

- Can the trigger cause the one-way hinge to close?

- Mathematical model

For the results of our experiments, check out our design and analysis.

Stretch goals

In this competition, we have aimed to produce a proof of concept of our system, by specifically working towards meeting the criteria for success set out above. To turn this proof of concept into a working product, there is still much work to do.

In the amplification system, we would like to modify the adaptor system to release the input DNA with the help of a fuel strand[7] and modify the amplification to be fourth order.

In the detection system, we focused on the hinges of the DNA sheet. The next step would be to add the brace, and demonstrate that when single-stranded, the brace is able to make the square twist close.

In addition, the amplification and detection systems were tested separately. For the ideal end goal to be achieved, we would have to test the amplification and detection systems together, ensuring that there is no cross-reaction between the systems, and that the amplified signal can be successfully passed from the amplification system to the detection system.

The last step, of course, would be to put the entire system into a chip, making it wholly practical. One might also experiment with modifying our system to target different viruses, or even other pathogens entirely!

References

- http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-08-21/flu-influenza-why-2017-has-been-a-particularly-bad-year/8826512

- Chonmaitree, T., Baldwin, C.D., Lucia, H.L. (1989). Role of the virology laboratory in diagnosis and management of patients with central nervous system disease. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 2: 1-14.

- Xuan, F. and Hsing, I. (2014). Triggering Hairpin-Free Chain-Branching Growth of Fluorescent DNA Dendrimers for Nonlinear Hybridization Chain Reaction. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 136(28), pp.9810-9813.

- Rothermund, P.W.K. (2006). Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature, 440: 297-302.5

- Andersen, E.S., Dong, M., Nielsen, M.M., Jahn, K., Subramani, R., Mamdouh, W. et al. (2009). Self-assembly of a nanoscale DNA box with a controllable lid. Nature, 459: 73-77.

- Jabbari, H., Aminpour, M., Montemagno, C. (2015). Computational approaches to nucleic acid origami. ACS Combinatorial Science, 17: 535-547.

- Zhang, Z. Fan, T.W. and Hsing, I.M.(2017). Integrating DNA strand displacement circuitry to the nonlinear hybridization chain reaction. Nanoscale, 9(8), pp.2748-2754.

Front page statistics

- Fisher M. Late diagnosis of HIV infection: major consequences and missed opportunities. Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 2008;21(1):1-3. doi:10.1097/qco.0b013e3282f2d8fb.

- Xia Y, McLaughlin M, Chen W, Ling L, Tucker J. HIV and Hepatitis C Virus Testing Delays at Methadone Clinics in Guangdong Province, China. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(6):e66787. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066787.

Icons made by Freepik from www.flaticon.com. Licensed for personal and commercial use.